Introduction

What can South Africa learn from other African countries in respect of upgrading or updating systems of customary or communal land tenure? At present the land rights of millions of South Africans who hold their land in the former homelands, in informal settlements and on transferred land are uncertain. The 1996 constitution, especially Section 25 (6) of the Bill of Rights, seemed to promise them enhancement and upgrading of their tenure. This has not been effectively done. Tenure is important because these largely African rural communities are amongst the poorest and it is important that their rights are not shouldered aside. For such families, their land rights are a major asset and they should be clearly recognized. Land tenure may also be one factor in improving rural livelihoods and in rural development.

At the outset we should acknowledge major differences between South Africa and most African countries. Firstly, a far smaller portion of the country retains these customary systems and they have been much modified by law and administrative practice. To the area of the former homelands, roughly 13-15 per cent of the agricultural land in the country, another 8-9 per cent has been added in the last 22 years. The latter is land that has been transferred from white to black ownership under the restitution and redistribution schemes. It is held through Communal Property Associations and Trusts, forms of collective ownership that differ from the systems of tenure in the former homelands, but which retain some similar elements in that individuals and families do not own their holdings.

Secondly, the proportion of the population and of landholders in urban areas is comparatively greater in South Africa and therefore the relevance of customary systems is less significant. It is difficult to estimate these numbers but at least 60 per cent and perhaps 70 per cent of landholdings are in urban and peri-urban areas, if informal settlements are included. The issue is complicated by the fact that some peri-urban areas fall within the boundaries of the former homelands where modified communal systems persist.

Thirdly, South Africa starts from a base in which private titled land tenure, registered at the Deeds Office, is more widespread than most, perhaps all, other African countries. This is by far the most widespread form of tenure in respect of the area covered. However, because the holdings in the former homelands, in informal settlements and on transferred land are often small, it may not be the majority system of landholding. One estimate suggests that 60 per cent of landholders have customary or informal title. Thus these 'off-register' forms of tenure remain of considerable importance, involving millions of families.

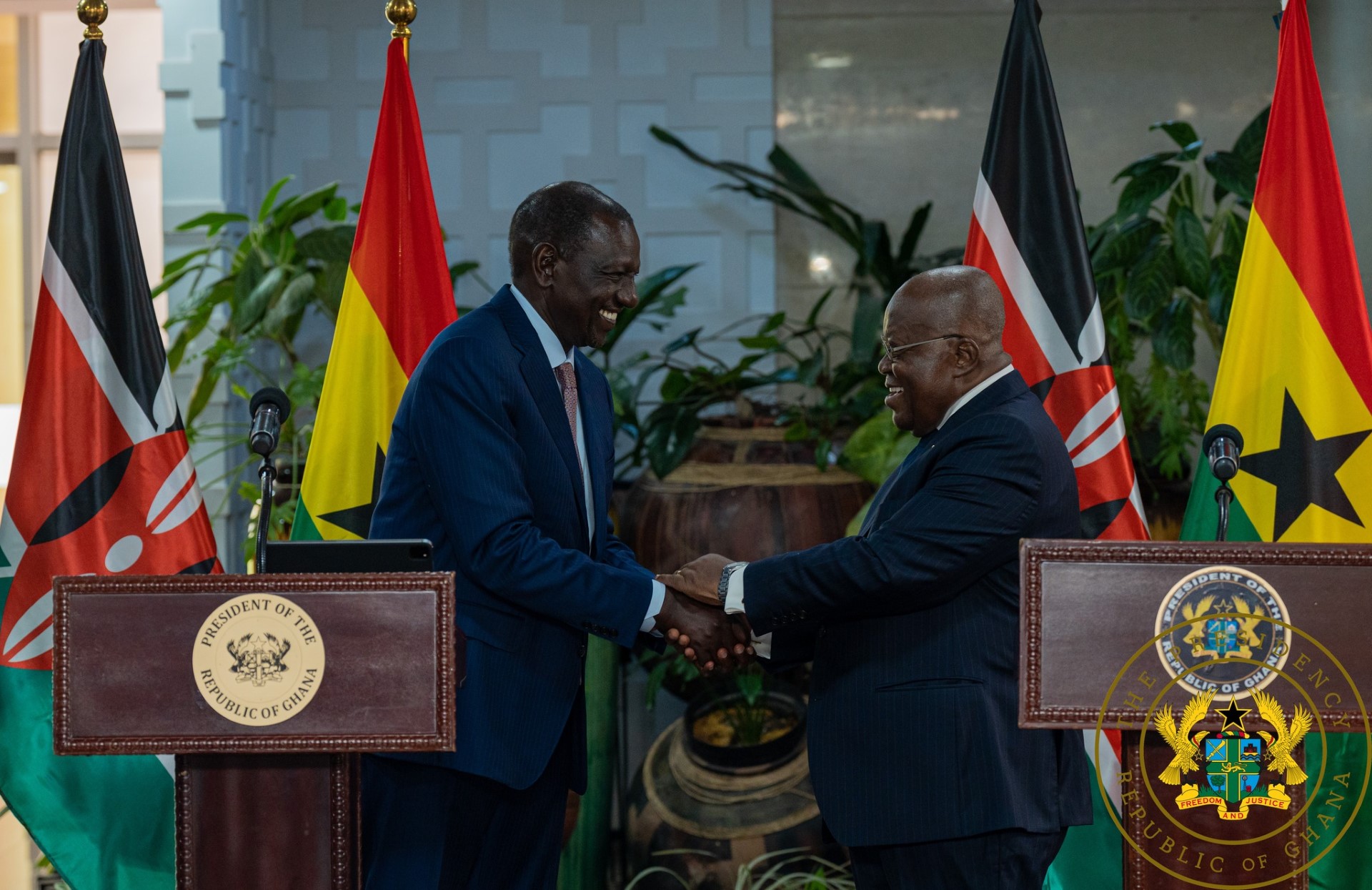

African countries have addressed the issue of land tenure in different ways. We examine briefly three different routes: a community-based policy in Mozambique; state-led privatization in Kenya; and customary control in Ghana which is increasingly leading to privatization from above.

A few countries, such as Kenya, opened up the possibility of private title for the majority of people soon after independence in 1963. Tanzania, by contrast, implemented a form of state-led collectivization through the ujamaa policy. The majority attempted to evolve the inherited forms of customary tenure, at least until the 1980s. In the 1980s, during the era of structural adjustment, both internal and external pressures led more countries in the direction of private systems of land holding or titling.

Since the 1990s and partly in direct response to the shift towards privatization, academics and activists have developed a more systematic defence of customary rights, acknowledging their diversity and also their dynamic and adaptive nature. Lawyers such as H. W. O. Okoth-Ogendo in Kenya and Patrick McAuslin in Britain were key figures in explicating customary law and arguing for its recognition - sometimes in hybrid policies. Issues of justice and equity shaped the new thinking about land policies. Privatisation or titling seemed to benefit elites and threaten the mass of citizens with exclusion from resources. Modified customary systems seems to give better access and more security to poorer landholders. There has also been extensive critical reporting on 'land grabbing' by foreign companies for plantations, mining and forestry - generally sanctioned and facilitated by African governments.

Alongside this critique of privatization of land in Africa, the question of tenure security has become a major issue in the international development arena. In 1999, the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements focused its activities on a global campaign for security of tenure. In other contemporary debates, tenure security is cited as a fundamental component for addressing Millennium Development Goal 7. Increasingly, titling has been seen as a route to insecurity for most poor rural landholders because they may be tempted to sell land in order to secure urgent cash needs. By 2009, the World Bank, formerly supportive of titling, had begun to switch direction. This brief survey takes note of such arguments, but suggests that they may not be the only solution for South Africa. A key question is whether customary tenure still protects the landholdings of poor rural people.

Mozambique

After the civil war ended in Mozambique in 1992, both international and national agencies were acutely aware of the importance of land in peace-making and the resettlement of disrupted communities. Following extensive consultation, a new Land Law was passed in 1997.[1] Christopher Tanner, who worked for the FAO in Mozambique, and was involved in the process of law making, has written extensively about the process and its results. The Mozambican system is rooted in customary law but allows for major changes. The constitutional basis is that the state owns all land in Mozambique, but that communities have strong rights over areas that they control. The 1997 law and subsequent regulations recognizes those rights and allows communities to control and manage their land, including customary practices, local agrarian activities, and new developments. Tanner writes that 'this approach had been advocated by the FAO advisory team not only because it matched the actual sociology of rural land use, but also because it offered a quick and cost-effective way of securing local land rights. One large unit could be surveyed and recorded, without the need for surveying and registering hundreds of small plots and other resources with complex, communal and common land characteristics.'[2] Although land is formally owned by the state, many local people thought of the land as theirs.

Community land is not alienable but outsiders can get access to land for 50 years (renewable). Communities must consent and a formal request to the state is also necessary to establish a right of use or DUAT. Improvements made by outside developers can be sold but neither the land itself, nor the DUAT, is transferable. This system was designed as a means of controlling the pressures towards privatisation, favoured by some donors and private sector interests. Private interests can get land for development, such as mining, plantations or tourism but generally have to include local communities in consultation, investment and development. The external users of land also have strong and defendable rights for a reasonable period of time. Those involved in developing the legislation were determined to move away from the old colonial dualism that segregated customary land, with little external investment, from privately-held and state areas. But it also meant that communities and individuals within them would (with their consent) give up areas of land that they might previously have used for smallholder farming and livestock. The result in theory is a cross-fertilisation of ideas and a system of mutual benefit between what might otherwise have been separate, protected, customary areas with little investment and 'private' zones where the bulk of external investment took place.[3]

There are similarities here to the position in South Africa. It is possible for those holding land in customary tenure to give up some of it for development. This has generally happened through the agency of the local chief and traditional council who have - to different degrees - been able to negotiate participation in the new enterprise. Platinum mining in Bafokeng, rooted in the homeland era, has been a striking example. Elsewhere, customary land was sometimes appropriated by the state and external investors in the homeland era - sometimes with the consent of the chief, but often without community consent. In the former Transkei, this included sugar, tea and forestry plantations, as well as national parks and a casino/holiday complex. A number of these cases have been subject of successful restitution claims. However, the legal basis of community control over land and external investment is not clear and is not effectively established in legislation.

The South African Communal Property Act of 1996 also has some analogous elements. Communal Property Associations (CPAs) were intended to be the main form of landholding for farms or state land transferred to communities through restitution and redistribution. The legislation also built on customary forms of landholding. CPAs generally hold land in private title but as a collective of beneficiaries and families who form a committee to manage the land. Initially they were largely designed for managing settlements of residential sites and agricultural smallholders but they have also become vehicles for developing more intensive farming operations. In some cases, restituted land already included established plantations and CPAs have negotiated with external companies to run them.

In Mozambique, some of the external enterprises envisaged large-scale development. ProCana Limitada--a sugarcane plantation project for biofuel-- was given a DUAT for 30,000 hectares of land and promised to employ thousands of Mozambicans.[4] The lease reportedly appropriated more than half of a community's land. In this case, there was not adequate consent and the scheme lasted only from 2007 to 2009 because of the collapse of oil prices. However, the more modest Covane Community Lodge was a successful example of the DUAT system. In 2002, the Swiss NGO Helvetas, in partnership with USAID, established a lodge on community land that could give easy access to the nearby Limpopo and Kruger National Parks. The project created employment opportunities and generated revenues for local suppliers to the lodge, as well as training for participants. Most successful projects have involved intermediaries such as NGOs who also help to take responsibility for the delimitation of community land and the DUAT contracts.

While the 1997 law has helped to entrench consultation and put a brake on infringements on customary land, Tanner felt, in his 2008 assessment of the first decade, that it was being bypassed or challenged both because of rapid growth in Mozambique and the changing character of the state.[5] Large investors, together with senior state officers, sought ways to bypass the system in awarding major contracts. The state is gradually taking more control, partly because of the size of projects with 85 involving more than 100,000 ha. Communities and even NGOs don't generally have the skills or experience to manage these. Big biofuel companies, for example, prefer to work through the state and such opportunities enable state officials to use their position. When a community environmental project with a safari company at Chipanje Chetu began to yield significant revenues, officials stepped in and decided to make the area a state-controlled forest reserve. In 2010 further legislation seemed to allow the local state to act as intermediary with external investors on behalf of communities.

Donor support, notably £15 million from DFID in the UK, has been important for the gains that have been made.[6] About 915 communities have been delimited, covering perhaps 25 per cent of the land; new World Bank funding promises a further expansion. But Tanner found limited political will for the policy in the central state, which tended to fast-track big projects and has come under criticism for facilitating large-scale external investment that involved moving smallholders - for example by the Mozambique Agricultural Corporation (Mozaco). The most ambitious project is a tripartite ProSavana agricultural programme between Brazil, Japan and Mozambique, initiated in 2009 and covering a possible 14 million hectares with millions of people affected. Although it is aimed in part at supporting existing farmers, the scale will require central management and appropriation of land. Reports on the web suggest that this has run into opposition and has largely stalled - although a few commercial soya bean farms have been launched.

There are parallels with external mining investment in South Africa where the combined interests of major corporations, state officials, Black Economic Empowerment consortia and local chiefs have on occasion outweighed protection of local land rights. However, the Xolobeni mining case in Bizana on the east coast, has also shown that a local community, with support from the Legal Resources Centre and broader civil society, can act to stop external mining companies and at least ensure full consultation.

Kenya

In Kenya, the late-colonial Swynnerton Plan (1954) had a significant long-term impact.[7] Land policy had previously tended to favour customary tenure and tribal reserves, focussing mainly on the white-owned highlands for intensive agricultural development. This plan argued for revolutionising African agriculture through consolidation of scattered plots, registration of individual titles and African access to the most profitable export crops, especially coffee. In South Africa, the Tomlinson Commission made similar proposals at the same time (1955) for development of the African reserves including privately-held 'economic units' of land as the basis for agricultural development. Tomlinson's recommendations were dismissed by Verwoerd who was intent on entrenching chieftaincy and concerned that enlarged farming units would drive many African people off the land and into the cities.

In Kenya, private land tenure was gradually extended after independence in 1963. One vehicle was the Million Acre scheme in the 1960s which redistributed a number of the settler farms on the Kenyan highlands.[8] Some of the land went as sizeable private farms of about 200ha. to political notables, but most went to about 30,000 smallholder families. A primary aim of the scheme was to give land to landless people who had been politically militant during Mau Mau and the struggle for independence.[9] Karuti Kanyinga notes that new settlements were to some degree ethnic in character and that Kikuyu settlers were the major beneficiaries. The land, however, was not free and over the longer term some recipients were evicted by the government because of indebtedness; some sold their land. This led to a gradual concentration of landholdings. As a whole, however, the scheme facilitated stability during the early years of independence and an expansion of production by African farmers.

Registration and private land also gradually spread on existing holdings. One of the best-known examples was illustrated by Tiffen, Mortimore and Gichuki in More People Less Erosion (1994).[10] They studied Machakos district, the Kamba area of Kenya, to the east and south-east of Nairobi. In the 1930s, it was recognized as one of Kenya's most degraded environments. But when they did their research in the 1980s, the district had been greened through intensive agriculture and investment despite a fivefold increase in population from about 240,000 to 1,300,000 and a doubling of livestock numbers from about 330,000 units (1930) to 593,000 (1989). At the same time, the area that was cultivated grew from about 15% in 1930 to over 50% in 1978.[11]

Generally this widely quoted book is taken as an argument against uncritical views that overpopulation leads to environmental degradation in Africa. Improvement is also possible. Yet one strand in their argument is less often stressed - private property was introduced into Machakos. The process was facilitated by the fact that customary law in the area gave very strong individual family rights. The first person to settle a smallholding effectively owned it and could leave it to sons, sell it or give it away. As population grew, privately owned farms gradually displaced the open grazing, and as early as 1938, the Local Council passed a resolution requiring people to fence or hedge both their arable holdings and their grazing areas. By 1990, at the end of the research, most of the grazing areas had also been privatised.

People in Machakos generally supported the registration of land that started in the 1960s; by 1977, 50 per cent of land was registered and by 1992 80 per cent. Registration was seen as a definition of land rights and a protection against powerful outsiders and local accumulators. In parts of Machakos, an active land market developed and land prices increased significantly, more rapidly than the population. Overall farm sizes declined but at the time of research 80 per cent of farms were over 1.6 ha. Investment into land increased with widespread terracing and cultivation, as well as fruit trees. Even though parts of the area were relatively dry, similar to areas such as South Africa's Ciskei, arable fields expanded greatly in number. In contrast, use of arable fields has declined for some decades in the former homelands of South Africa. This is not simply the result of the persistence of customary tenure and PTOs, but the experience in Machakos indicates that privatisation of land can be associated with intensification. The process was facilitated by strong local support for registered land, the focus on coffee in suitable areas and the closeness to Nairobi.

By contrast, South African policy has failed dismally in encouraging investment into smallholder agriculture. The reasons are complex and are not only related to tenure. However, the decline in smallholder agriculture applies both to the homeland era during apartheid, when chieftaincy and communal tenure were entrenched, and to the democratic period since 1994. The spatial organisation of settlement in the former homelands of South Africa makes it very difficult for African landholders to control their arable fields adequately or to consolidate farms. In South Africa, there has been little or no experimentation with the Machakos model where grazing lands have been subdivided to become part of individually owned farms. Family ownership of land has not been facilitated, although a market in sites has developed in some customary areas.

However, the process of private titling in Kenya was uneven. Anzetse Were writes that 'while there may be a general acknowledgement by their community that the land they farm is indeed theirs, the costs related to registering land and acquiring titles are too high for most smallholder farmers'.[12] Were argues that these constraints on titling have begun to hamper investment. State institutions don't have the capacity to issue formal titles for registered land and Wily estimated that by 2014, over a million were pending.[13] Were also suggests that communal land is more likely to suffer land grabs by the powerful if ownership is not clear. As in Ghana, discussed below, there may be privatization from above if there is not privatization from below - or at least state and judicial recognition of very strong protection in customary law for family and individual land rights.

By no means all agree with this assessment of Kenya's land issues and there were clearly areas where titling was resisted or proved unsuitable - particularly drier pastoralist zones in the north. Ambreena Manji takes a different view, arguing that issues of equity in access to land have been neglected in the constitutional reform.[14] The National Land Policy formulated in 2009 and the 2010 constitution promised a transformative approach, including both security for landholders and effective administration. But Manji argues that the various land related Acts passed in 2012 'marked continuity with the past and the basic tenets of neoliberal land policy, for example by promoting land markets, providing for the individualisation of land tenure, and enshrining in law a presumption against customary tenure'. Manji is more generally critical of the new wave of law reform seeing land as 'a tradeable asset that can be used to leverage loans' and opening the way to further accumulation and the use of land as patronage. Public land has been appropriated by those with political power and often sold on.

Kenya's constitution and Land Act of 2012 appear to provide both for collective or community ownership and to protect private property rights. The Act specifically states that customary land rights have equal recognition with freehold and may not be discriminated against. Implementation has, however, run into problems because so many areas are either public land (for example conservation areas) or privately held land. There have also been problems of specifying the level of the community involved - and how this relates to local government areas. Community claims are likely to be by those who have a heritage as pastoralists or hunter-gatherers - though they may no longer subsist in this way. Their claims may largely be outside of the major agricultural zones but boundaries are difficult to specify and overlap with other forms of landholding,

Ghana

Literature on land tenure in Ghana emphasizes the persistence and extension of chiefly control. Sara Berry notes that in both Ghana and South Africa chiefs have adapted effectively to new power structures, although in different ways.[15] In Ghana, chiefly control over land seems especially effective. During the early colonial era, chiefs in the major British West African colonies of Ghana and Nigeria fought against state authority over what they considered to be their land. These and other battles helped to shape the policy of indirect rule, which was by no means simply a British imposition. The Oluwa land case in 1921, when a Nigerian chief won a Privy Council judgement against the colonial government, helped to shape British policy in West Africa. Although land around Lagos was becoming partly privatized, the court set down a 'doctrine of chiefly "trusteeship" over the "native community"'.[16] On the one hand, this prevented the state from taking direct control; on the other hand, it provided a reference point that gave traditional leaders a central role. In Ghana, chiefs were seen as allodial holders of the land - that is owners of land in the last resort, not direct possessors or freehold owners.

Nkrumah was ambivalent about the power of chiefs immediately after independence, but the military rulers in Ghana from 1966 tended to accommodate them and in 1979, when Rawlings took power in a coup, the government recognized chiefly control of land throughout the country. Chiefly status, separate from the state, as well as their authority over land, was confirmed in the 1992 constitution under which Rawlings took power as an elected civilian president. Chiefs control about 80 per cent of the country, including areas in which key commodities are produced, and they have been able to use their position to generate income from leases, taxes and direct involvement in commercial enterprises. In effect, there has been a gradual privatization from above as control and allodial rights have transmuted to a form of ownership of these stool and skin lands. Chiefs can sell land, and it can also be bought and sold between holders but the residual ownership by chiefs remains. Old-established rights over forests have also enabled chiefs to act as intermediaries in environmental interventions, projects and logging.[17]

Sara Berry noted, however, that chiefs have avoided promoting legislation in this area and avoided a direct role as political representatives in national politics as they do not wish to be subject to elections. But they have defended their position successfully in court cases based on the 1992 constitution and used their control over land and local judicial authority to build political networks and influence within the state. Berry argues that the position and strategy of Ghanaian chiefs has differed from that in South Africa where traditional leaders were more directly involved in the bureaucracy during the homeland period and seem to be trying to insert themselves in local government again. In South Africa, however, the position of chiefs in relation to land is less certain and has relevance to a much lower percentage of land. They may claim authority in many of the former homeland areas but this is not everywhere accepted. The political authority of traditional leaders is now subject to new policy measures that could be of central importance for the future of the country.

But there are also similarities. Both countries have formal institutions connected to the legislature such as national Houses of Chiefs; in both countries chiefs try to be leaders of local development in the name of the communities that they claim to represent. And some chiefs in South Africa are attempting to move in the Ghanaian direction. The Zulu royal house secured the Ingonyama Trust Act (3 of 1994), which effectively placed it in control of all land under the former KwaZulu homeland and opened the possibility of extending this area. This, together with political recognition of the Zulu royal house, was effectively the cost paid by Mandela and the ANC to bring the Inkatha Freedom Party into the national democratic dispensation in 1994. The position in other former homelands in not clear, but some chiefs are attempting to control external investment, especially by mining companies, in areas where they claim authority. The Royal Bafokeng Platinum company is the best-known example.

Kojo Amanor argues that this commoditization of land in the hands of chiefs has been intensified rather than undermined in Ghana by structural adjustment and international investment over the last few decades. Liberal reform has given legitimacy to expanding private rights; the World Bank and donors prefer efficient land markets. Chiefs themselves are often well-educated and adept at negotiating these new social forces and 'have their own lawyers and iPads'.[18] Moreover, they have made appeals to tradition and cultural heritage, which the national media tend to reflect as a moral good.

Chiefly control over land has also been significant in peri-urban areas as Ghanaian cities expanded rapidly. Janine Ubink describes how, in peri-urban areas around Kumasi, the second largest city, with a growing demand for residential property, chiefs have redefined customary tenure in a way that enables them to dispossess farmers and sell land to urban buyers.[19] This was not a foregone conclusion in that different levels of chieftaincy were often in competition, and there was also some oversight by the state and municipal authorities. Nor has it been uncontested. Ubink notes that there is some local resistance against chiefs' maladministration of land but it is limited by the political authority of chiefs, who also tend to control local courts and customary law. The state tends to support traditional authorities and 'chiefs are often the main beneficiaries of land conversions'.

A system of land registration was renewed by legislation in 1986 and by a national Land Administration Project since 2003, supported by the British DFID. It aims to certify popular rights over customary land and enhance tenure security of smallholder farmers. Reports suggest that it has made limited headway because of the costs of survey and registration as well as disputes. Chiefs found a way of inserting themselves so that they had to sign off the certificates. Registration is being decentralised to Customary Land Secretariats that are associated with traditional rulers.

Ubink and Amanor argue that the government has decided to work within the existing power structures of chieftaincy rather than to attempt to create a more democratic framework for land management that is administered directly by the state.[20] 'In matters of land allocation', they write,' chiefs' authority has become virtually unchecked: in recent large-scale acquisitions of rural land, buyers negotiated directly with paramount and divisional chiefs, while government officials stood aside, invoking the constitutionally-recognized principle of non-interference in chiefly affairs'. The state does not generally enforce payment by chiefs of rentals from stool lands into accounts that should be used for local government expenditure. Officials recognize the influence of powerful chiefs and consult them on land use planning.

Some Conclusions

Land tenure is a complex area and there are often different and overlapping forms even within the same country. This brief summary is based on limited sources and discussion at workshops in Cape Town and Oxford in 2016-7. It is difficulty to gain an overview even of the South African situation, with which I am more familiar, based on published sources. Processes on the ground do not always reflect the formal legal position. There may be other interpretations of these national contexts that are not adequately reflected here.

Customary tenure can offer wide access to land and some degree of security. But in Ghana chiefs appear to have gained a pivotal role and to dominate customary systems to their own advantage. There are signs of the Ghanaian path in South Africa, with chiefs and traditional councils acting as intermediaries for external investors and effectively privatizing areas of the land held in trust for communities. With respect to mining, the requirement that 26 per cent of new enterprises should be controlled by Black Economic Empowerment beneficiaries tends to accentuate these developments. However, there are also contexts where traditional councils act as distributors of land rather than accumulators.

In Mozambique, community control of land has been more effectively recognized but family landholdings seem to be threatened, in some cases, by a combination of state and corporate enterprises. This suggests the weakness of collective control of land for protecting the rights of smallholder families.

The lessons I draw from these two comparative cases is that the government and constitutional court in South Africa should make a clear and unambiguous statement, or law, that family holdings in the modified customary systems and CPAs are very strong and akin to ownership. Families and individuals should be able to defend their holdings against the state, chiefs or private interests. If they consent to give them up for some overarching public purpose they should have full rights to compensation, akin to sale.

The question arises as to whether registration, and private title, are the best routes to further upgrade such rights. This cannot be discussed fully here. Registration has been attempted in African countries but it is a major exercise, difficult to keep up to date, and subject to influence by those with local power. Titling usually requires survey and other costs, which can be expensive for poor smallholders. Private title in Kenya has not always guaranteed security and has led to accumulation of land. However, landholders can benefit from sale of their land in private systems.

Neither customary tenure nor registration and private title are unambiguously effective in providing security for poorer landholders. However, the Machakos model did seem to have combined effective and widely supported registration, titling with continued widespread access to land and investment in smallholder agriculture. In Kenya smallholders have, to a greater degree than in the communal tenure areas of South Africa, been able to consolidate and fence farms around a homestead. I would strongly advocate a pilot scheme along the lines of that described for Machakos (up to 1990) in both a communal area and a CPA in South Africa. Kenyan routes are in certain respects promising and would help to cement a single landholding system in South Africa in the long term. However, strong institutions are essential to curtail corruption and prevent private takeover of public land by political elites.

[1] Christopher Tanner, Law-Making in an African Context: The 1997 Mozambican Land Law, FAO Legal Papers Online, 26 (2002)

[2] Tanner, Law-Making, 34

[3] Tanner, Law-Making, 48

[4] Anna Knox and Christopher Tanner, 'Brief: Community Investor Partnerships in Mozambique', Focus on Land in Africa Website

[5] Christopher Tanner, 'Implementing the 1997 Land Law of Mozambique: Progress on Some Fronts'; and his presentation at Mokoro seminar, Wolfson College, Oxford, March 2017

[6] Christopher Tanner, Presentation at Mokoro seminar, Wolfson College, Oxford, March 2017

[7] R. J. M. Swynnerton, The Swynnerton Report: A plan to intensify the development of African agriculture in Kenya (Nairobi: Government Printer 1955).

[8] Karuti Kanyinga, 'Kenya experience in Land Reform: the 'million-acre settlement scheme', paper on web.

[9] Christopher Leo, 'Who Benefited from the Million-Acre Scheme? Toward a Class Analysis of Kenya's Transition to Independence', Canadian Journal of African Studies, 15, 02 (1981), pp. 201-222

[10] Mary Tiffen, Michael Mortimore and Francis Gichuki, More People Less Erosion: Environmental Recovery in Kenya (Wiley, Chichester, 1994).

[11] Tiffen, Mortimore and Gichuki, More People Less Erosion, p. 5.

[12] Anzetse Were, 'Iron Out Key Land Issues to Unlock Growth Potential in Kenya', article on web.

[13] Liz Alden Wily, 'The Community Land Act: Now it's up to communities, The Star, 17.9. 2016 (thanks for Ambreena Manji for the article).

[14] Ambreenja Manji, 'Whose Land Is It Anyway? The failure of land law reform in Kenya' Counterpoints; Ambreena Manji, 'The Politics of Land Reform in Kenya 2012", African Studies Review, 57, 1 (2014).

[15] Sara Berry, 'Chieftaincy, land and state in Ghana and South Africa', unpublished paper circulated for the workshop on Chieftaincy, LARC, Cape Town, May 2016 and verbal contribution.

[16] M.P. Cowen and R.W. Shenton, 'British Neo?Hegelian Idealism and official colonial practice in Africa: The Oluwa Land case of 1921', The Journal of Imperial and

Commonwealth History, 22, 2 (1994), 217-250

[17] Richard Grove and Toyin Falola, 'Chiefs, Boundaries, and Sacred Woodlands: Early Nationalism and the Defeat of Colonial Conservationism in the Gold Coast and Nigeria, 1870-1916', African Economic History, 24 (1996), 1-23.

[18] Kojo Amanor, 'The changing face of customary land tenure' in Janine M. Ubink and Kojo S. Amanor (eds.), Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen and presentation at the workshop on Chieftaincy, LARC, Cape Town, May 2016

[19] Janine Ubink, 'Traditional Authority Revisited: Popular Perceptions of Chiefs and Chieftaincy in Peri-Urban Kumasi, Ghana', The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 39, 55 (2007), pp. 123-161; Janine Ubink, 'Struggles for land in peri-urban Kumasi and their effect on popular perceptions of chiefs and chieftaincy' in Ubink and Amanor (eds.), Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen, 55-82.

[20] Janine M. Ubink and Kojo S. Amanor, 'Introduction' in Ubink and Amanor (eds.), Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS