The shortage of a dermatologist in some areas makes it impossible for nearby women to get a timely diagnosis

A new report finds that swaths of pregnant women are having to wait too long for treatment of deadly melanoma. The lag puts not just one, but two lives at risk.

In September, Women’s Health published a troubling report about the dangerous repercussions of a nationwide shortage of dermatologists. One in five areas of the country don’t have a single dermatologist within 50 or even 100 miles, and in these areas—which we dubbed “derm deserts”—there are more melanoma deaths. The shortage makes it impossible for nearby women to get a timely diagnosis, and when you have melanoma—the most aggressive form of skin cancer—waiting a few months, or even weeks, for an appointment can be fatal.

Now, we’re getting hit with more bad news: Pregnant women may be particularly vulnerable.

A new study published in the journal JAMA Dermatology looked at more than 7,600 North Carolina residents who had been diagnosed with melanoma. Researchers found that those with Medicaid insurance—which covers around half of all pregnant women in the U.S., or 2 million pregnancies per year—were 36 percent more likely than those on other insurance plans to experience a delay of more than six weeks for the surgical removal of their cancer. Yet research shows that patients should be treated within two weeks for the best chance of survival. Six weeks is the recommended maximum wait time; once melanoma has spread, it’s much harder to treat. And pregnant woman with melanoma may be at greater risk for complications from the disease than nonexpecting women. (Though the study was done only in North Carolina, researchers say this data can be extrapolated to the entire country—where things might be more problematic: According to our investigation, North Carolina is far from the worst of the derm-desert states; in contrast, the entire state of Utah is a desert.)

WHAT’S HAPPENING WITH MEDICAID

The government-funded health insurance program is set up to help low-income people and families, pregnant women, and those with disabilities. Many states offer Medicaid to pregnant women with higher incomes than nonpregnant women (even incomes that hover around the national average for young women) because they’re considered a “needy” group by the U.S. government. So if they’re covered, why can’t they get their melanomas removed? Experts suggest two troubling theories:

Many doctors aren’t taking Medicaid patients. “We have a real access-to-care issue,” says Sapna Patel, M.D., a melanoma oncologist at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “Women who call the Medicaid community health center for a derm referral might have to wait months for an appointment and then also experience a delay in treatment.” One study found that only 32 percent of U.S. dermatologists accept new Medicaid patients. This may be because Medicaid reimburses doctors only a fraction of what private insurers do and takes longer to process those payments, studies show. Women’s Health contacted Medicaid for comment, but there was no response as of press time.

Pregnant women on Medicaid have to jump through medical hoops. The JAMA researchers surmise that Medicaid patients could be waiting longer for surgery because of poor coordination of care. Think of it this way: Fewer derms mean you might have to get a diagnosis from a PCP. At that point, you’ve got to find a dermatologic surgeon—those, too, are few and far between on Medicaid. That person has to be able to fit you in ASAP. Yet they may not, because, as one derm told us, a diagnosing dermatologist will see her own patients more quickly than new people. All of this explains the finding of multiple studies: that when a general-care doctor or other health-care aide, versus a derm, diagnoses a melanoma, there are longer excision delays.

A SPREADING CONCERN

Almost a third of melanoma cases are diagnosed in women during their childbearing years. One explanation: The sun damage we acquire as kids usually pops up 10 to 20 years later, says Patel, putting women in their twenties and thirties at risk. Once pregnant, many women don’t prioritize skin checks. They are likely more concerned with seeing their ob-gyn than, say, having a new mole on their leg checked out and subsequently getting a prompt diagnosis, says Patel. It’s true that melanoma in pregnant women is quite uncommon, but when it happens, it can be serious.

Biologically, pregnancy itself may trigger melanoma for some women. Pregnancy decreases the efficacy of the immune system. “This is nature’s way of preventing the body from rejecting something ‘foreign’ and protecting the fetus—but we rely on that immune system to protect the body from things like cancer and melanoma,” explains Patel. “In some cases, melanomas can emerge due to what we call ‘immune escape,’” meaning they sneak through the gates while the immune system is compromised.

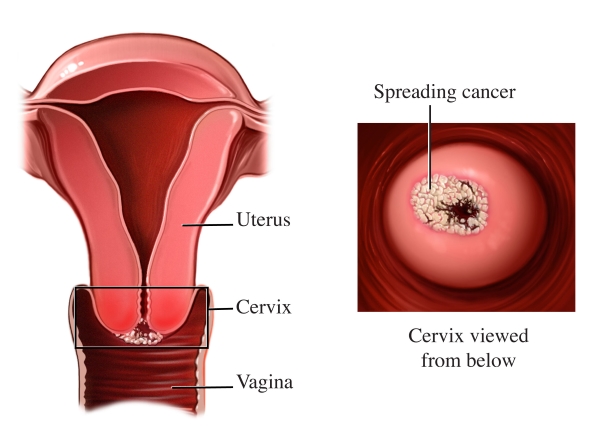

This immune suppression can also make melanoma more dangerous. “While there’s a lot we don’t know, we see concerning patterns with melanoma being diagnosed at a more advanced state, and progressing faster in pregnancy,” says Patel. A 2016 study, from the Cleveland Clinic and published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, found that women who were diagnosed during or shortly after their pregnancy were significantly more likely to have tumors spread to other organs and have the cancer return after treatment.

Another hypothetical reason for melanoma growth in pregnant women: estrogen. “We’ve had a hunch that, though melanoma is not hormonally driven like breast cancer or ovarian cancer, there could be hormonal factors that contribute, especially during pregnancy, to skin changes,” says Patel. It’s a fact that pregnancy can bring on melasma, dark spots on the face, so “we know that hormones are already doing things to the pigment itself in the body,” Patel continues. Currently, there’s no data proving that extra estrogen is causing or accelerating melanoma in pregnant women, but researchers are interested in studying this.

TWO LIVES IN JEOPARDY

When melanoma metastasizes, or spreads to other organs or lymph nodes, it requires more complex treatment options. Some of them—like immunotherapy, more effective than chemo for late-stage skin cancer —can’t be used during pregnancy because they could put the baby at risk for an autoimmune disease. “If a patient has metastatic melanoma and is in her first or second trimester, it’s unlikely she’ll be able to deliver to term without the melanoma becoming very life-threatening,” says Patel. Earlier this year, a 30-year-old New Jersey mom died just three days after an early delivery at six months pregnant, and three weeks after her diagnosis, from metastatic melanoma that had spread throughout her body while pregnant.

And though it’s extremely rare, melanoma is one of the few cancers that can cross over from the mother into the placenta, affecting the baby. “It’s tragic when this happens because the baby will usually develop melanoma within the first year of life, and because the disease is advanced, it’s always fatal,” says Patel.

PROTECTING MOM AND BABY

If there is good news, it’s that if caught early—and in general, most melanomas are—cancer that’s localized to the skin doesn’t generally put a pregnant woman or her baby at an extra risk, says Justin Ko, M.D., director of medical dermatology at Stanford Health Care and clinical associate professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. Physicians (both dermatologists and many primary-care docs) can safely perform skin biopsies with local anesthetic during pregnancy, which is why it’s key to have regular skin cancer checks (especially if you’ve had it in the past) and report suspicious moles to your M.D.

For those struggling to get an appointment, it’s crucial to be specific when calling a derm’s office. Tell the receptionist you’ve been diagnosed with melanoma and need a removal ASAP, and if you’re pregnant, make sure to mention the situation is particularly time-sensitive. If that doesn’t work, demand to speak with a doctor or nurse, and be persistent.

The shortage of a dermatologist in some areas makes it impossible for nearby women to get a timely diagnosis Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS