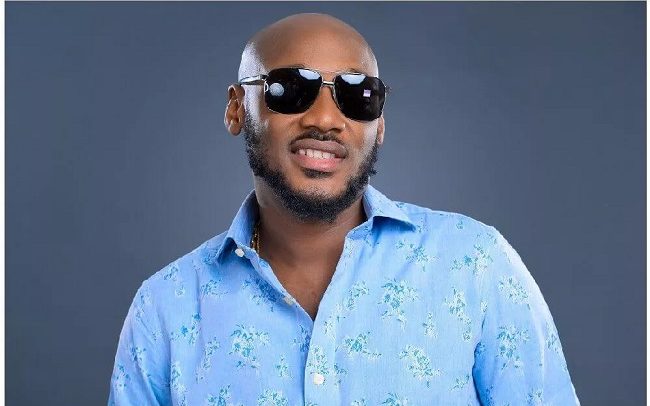

Alicia Hupprich used this photo to announce her pregnancy before she realized her daughter had a serious heart defect and was faced with the difficult decision of whether or not to terminate.

The House just voted to outlaw abortions after 20 weeks. Here's why one woman says that's not right.

My husband and I began trying for our second child in the spring of 2015, and that May, we learned we were pregnant. We'd conceived our first child quickly and without incident, and this time was no different. I still have the video on my phone of my 2-year-old daughter running up to my husband with a positive pregnancy test in a shirt that said "I'm going to be a big sister." Our family was so excited—my daughter was even talking to my belly.

At 18 weeks and three days, my husband and I went in for an anatomy scan ultrasound, a standard procedure where they check to make sure the baby has all of its appendages, organs, fingers, and toes. When I went into the appointment, I thought the most important thing I’d learn was whether we were having a boy or a girl—something I feel naïve admitting now. When they told us it was a girl, I was elated and started crying, saying that my daughter would have the sister I never did.

But the technician kept going back to our baby’s heart, which made me nervous. She said something was wrong and that she was going to get the doctor. Those 45 minutes she was gone were agonizing. My tears of joy turned to tears of panic, and my mind was reeling over what could be wrong with our baby.

When the technician reappeared with our doctor, we learned that our daughter had a thick white lining on her right ventricle, which they said might be a sign of hypoplastic right heart syndrome, a very dangerous condition that prevents the heart from forming properly. They said that if this was the case, our daughter would certainly need a heart transplant —but that a series of surgeries could buy time until that operation become necessary.

At that point, the doctors noted that termination was an option, which was an overwhelming thought to digest after having just being told something was wrong 45 minutes prior. When the pediatric cardiologist came down to see us and explain the condition further, he was shaking like a leaf. That was a big red flag.

At the end of that day, the doctors said they couldn’t offer us an official diagnosis because our baby's heart was still so small. They also said that there were some indications that it might not be hypoplastic right heart syndrome at all, but regardless, it was something to be taken seriously. So they had us book another fetal echo appointment for three weeks later. The not knowing left us feeling frustrated and helpless, but all there was to do was wait and learn as much as we could about our baby's condition.

We went home with literature on the condition and started thinking about what kind of quality of life our daughter would have—what this would mean for her and our family. We were looking into all of our options at this time, and I sent the doctors an email with at least 20 questions. A few of these were geared toward the option of termination, asking what that would entail if we did choose that route.

The response I got was that if we wanted to terminate, it would be “out of network”—meaning the hospital would not be able to perform the procedure, and that my insurance wouldn't cover it. A little backstory here: My husband is in the Coast Guard and we were getting care from a military hospital. I was also covered by his insurance at the time, and The Hyde Amendment (a provision of Roe v. Wade that bars federal funds from being used for abortion) doesn’t allow military healthcare providers to perform or insure abortions. I don't want to speak ill of anyone at the care facility; it wasn't that they were unhelpful or unkind, it was just that, when it came to the question of terminating, they made it clear their hands were tied.

Seeking A Second Opinion

I decided to get an outside opinion before going back for the second scan. By the time I was able to get an appointment, I was 21 weeks' pregnant. We were told the doctors saw that same white lining on the left ventricle of her heart, as well as on the mitral valve, the part of the heart that pumps blood out toward the lungs. This ruled out the previous diagnosis of hypoplastic right heart syndrome. The doctors told us that having a complication on the left ventricle was concerning, and that the spreading of this white lining on the right and left ventricles was essentially unfixable.

When we went back to our original hospital at 21 and a half weeks, we found out there was even more thick, white lining—basically, the walls of our baby’s heart looked like what a skull would look like on an ultrasound. Every doctor who we saw said there was no medicine to fix this and that there was little they could do.

As a sort of Hail Mary, we decided to go to a children's hospital in Pennsylvania for a third and final opinion.

This is what a future without legal abortion would look like:

The Decision

The five weeks leading up to that final appointment were hell. I would put my 2-year-old to bed and stay up until 1 a.m., pouring over medical journals. I wanted to make the best decision possible for our baby and for our family. If there was a chance of a positive outcome, if there was some specialist somewhere who could solve our daughter's heart issues, I wanted to find them and see them. At the same time, I had to research the alternative option of termination. It wasn’t like I was six weeks' pregnant; I needed to know exactly what this procedure would involve, where we would go, and how we would pay for it.

Fortunately, one of my closest friends had started an abortion fund in New Jersey while she was living there, and she referred me to the National Abortion Federation website. Abortion funds help women cover the out-of-pocket costs of abortion, as they're often not covered by insurance.

As I was making appointments to get second and third opinions on my baby, I was also calling abortion clinics in the D.C. metro area, in Maryland, and in New Jersey. I couldn’t go anywhere in Virginia because there’s a state law that any abortion performed after 12 weeks must be performed in a hospital, and as a family on a single military income, with a child, we couldn’t afford the $20,000 bill that would come with an induction abortion at a non-military hospital. Nor did we even know of a civilian healthcare provider that could help us with that. I felt like I had no support from the medical community.

Another option we looked into was carrying to term and then admitting our daughter to perinatal hospice care, but our research revealed that those caring for her would have the power to decide if they should keep her alive by any means necessary, despite her discomfort. And if we objected to it, we could be charged with child abuse or neglect and could even lose custody of our oldest daughter. Knowing that, we didn’t feel we could risk carrying our baby to term and doing perinatal hospice.

Ultimately, our greatest concern for our unborn daughter was what her life would look like. Life is so much more than just having a beating heart and oxygen in your blood. We did not want to put our child through a life consisting only of pain. We knew at that point that, in order to give her the most peaceful life possible, we had to take all the pain on ourselves.

By the time we made it to our third hospital appointment, I was at 23 weeks exactly. After eight hours, five of which were spent ultra-sounding, we learned that the dead tissue that was causing her heart to fail had spread even further. It was on three out of the four chambers of her heart. They also found fluid collecting outside of her heart, which was likely turning into fetal high drops, a condition that is in and of itself dangerous and has a very high mortality rate. When you couple that with a heart defect, there is almost no chance a baby will survive to term.

There, they told us that if she made it to birth, the damage that she had on her heart would cause her difficulty breathing, heart attacks, seizures, and strokes due to a lack of oxygen getting to her brain. It sounded like a nightmare, like something you’d experience as an 88 year-old man, not a newborn baby. Our longest shot would have been a heart transplant at birth (if she made it), which means we'd be waiting on someone else’s baby to die so ours could live.

The Procedure

Truthfully, we knew going into that final appointment in Pennsylvania that it would take a miracle to change the outcome for our baby, so we made an appointment for a dilation and evacuation (D&E) at a clinic in New Jersey to coincide with that trip.

It was important for us to make the appointment there for a few reasons. For starters, many places in D.C. cut off abortions at 18 weeks, even if they're medically necessary. By comparison, there are three clinics in New Jersey that offer abortion up to 24 weeks, including the one we went to. This clinic also offered full anesthesia, which was important to me, as I didn't want to remember the procedure. We were also able to receive some assistance for the $3,000 procedure from the abortion fund that my friend had set up.

We drove from Philadelphia and had to get a hotel in New Jersey for the two-day procedure. The first step would be dilating my cervix, for which I'd be awake, and the next day, they'd "evacuate" the fetus while I was anaesthetized. I remember standing at the check-in desk thinking, This can’t be really happening. When we pulled into the clinic, there were protestors outside, and I was a major target, being as far along as I was. Even in the waiting room, I was getting looks from everyone. I probably broke down crying four or five times just sitting there. There wasn’t any privacy, so I couldn’t rub my belly or sing to my baby in order to enjoy those last hours with her.

The first day of the procedure started with an ultrasound to make sure everything was normal and ready for the procedure. Then, they administered a shot of digoxin into the uterus, which slowed and eventually stopped the baby’s heart. It took about three hours before she stopped moving. Those hours were excruciating and seemed to crawl by. I felt completely devastated. Then, they inserted the laminaria, which helps the cervix expand for labor and sent us on our way. In total, I was there for about six hours.

That night, the laminaria caused a lot of cramping. The next day, we went in early and I was one of five women taken back to a little locker room-like exam room to wait. It felt like none of us were getting the privacy we deserved, not at the fault of the doctors or nurses, but because the resources were so limited. All of the nurses and doctors there were incredibly compassionate, maybe some of the most compassionate medical professionals I’ve seen. They gave us Cytotec (a hormonal medication that stimulates the uterus) that morning, which I’d actually had with my first labor and delivery when I was induced. We were all sitting in the room together, and my contractions started to come more regularly.

The staff started taking each woman back, one by one, into the pre-op room to get into the gowns and be hooked up to I.V.s. Then it was my turn. The next thing I remember, I woke up in the recovery room, which had several other women in it, as well. I remember being in a lot of pain. They gave me some crackers. It was really no different than the recovery after my first daughter’s birth. Afterward, I kept asking if my husband knew I was okay because, at that point, he was at the funeral home signing all the paperwork to have our daughter cremated.

We were very fortunate to have a clinic that worked with a funeral home in the area so we were able to get remains. Not everybody is able to do that.

The Recovery

We were sick with grief for several months after the procedure. After our termination, the clinic gave us a mold of our daughter's footprints, which I really appreciated. I used to hold those footprints up to my cheek and just cry because that was the closest I could come to touching my baby. The footprints and remains are the only tangible things I have of her. I sought out grief counseling and was fortunate enough to get that through my husband’s employee assistance program. My therapist specialized in perinatal loss and was wonderful.

Because we never received a firm diagnosis on what was wrong with our daughter, we continued searching for a medical cause through genetic testing; we wanted to know the likelihood of this happening if we tried to get pregnant again. We found that I had SSA/SSB antibodies that are typically linked to rheumatoid arthritis—but while this could have caused a minor heart defect, the doctors said our experience was basically a fluke.

After eight months, we felt brave enough to start trying for another baby. We were fortunate to get pregnant quickly, but after that, it was nine months of holding our breaths.

We had 20 echocardiogram exams done, and countless ultrasounds. It was intense, and I also had to monitor my baby's heart twice a day through a doppler, a machine that lets you listen to the baby's heartbeat at home. I was put on Plaquenil, a immunosuppressive typically used to treat lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, to keep the antibodies from attacking the baby's heart. We were very lucky this time around, and now we have a healthy six-month-old baby.

Protecting My Choice

I’ve always been pro-choice, but I was one of those women who'd conveniently say, “I’m pro-choice, but I don’t think I’d ever make that decision for myself.” I realize now what a narrow-minded way of looking at things that is. I certainly didn’t think that, as a grown woman in a stable relationship with the means to support myself, I’d face abortion. But it comes in all different circumstances, each one of them valid.

This week, the House of Republicans voted to pass the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, a bill that bans abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy. The bill proposes penalizing those who perform the procedure, rather than the women who receive it. House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy claims that this legislation "will respect the sanctity of life and stop needless suffering" based on the controversial claim that a fetus can feel pain at 20 weeks. Next, the bill will go before the Senate.

Abortion after 20 weeks is a tragic circumstance, and no woman who makes that decision takes it lightly. You can’t even imagine the pain and heartache that goes into making that decision until you face it yourself. We would be jeopardizing women’s health by restricting this and targeting families who are experiencing the worst crisis they’ll likely ever face. The decision I made was similar to a family choosing whether or not to take a child off of life support. Just like we shouldn’t force women who face poor prenatal diagnoses to terminate, we shouldn’t force women to carry to term, either. It’s a complicated decision—and we shouldn’t shame families for having to make that decision.

Alicia Hupprich used this photo to announce her pregnancy before she realized her daughter had a serious heart defect and was faced with the difficult decision of whether or not to terminate. Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS