By Harold Kwabena FEARON

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the world in profound ways, and the countries that act decisively today will shape the direction of global innovation for decades to come. From rapid advancements in generative AI to the deployment of machine learning in health, agriculture, education, finance, and public services, AI is no longer a speculative technology.

Around the world, nations are racing not just to harness AI’s economic potential but also to build governance systems that ensure safety, ethics, and accountability. In this global contest, governance has taken center stage in the story of technological transformation.

As African countries embrace a wave of digital innovation, there is an urgent need to reflect on how leading economies are structuring AI governance and what lessons Ghana can derive to lead this charge. Understanding the models that work elsewhere is critical if Ghana is to build an AI ecosystem that protects its citizens, encourages creativity, and promotes sustainable development.

Therefore, this article intends to explore what Ghana can learn from global AI governance frameworks, why Ghana is uniquely positioned to lead in Africa, and what strategic steps the country must take to build a robust, human-centered governance architecture.

The global AI governance landscape

Globally, AI governance has become a high-stakes project. The European Union’s AI Act is perhaps the most developed example: it proposes a risk-based classification system in which AI applications are categorized by their potential harm, ranging from minimal risk to unacceptable risk.

High-risk systems will be subject to mandatory conformity assessments, transparency requirements, and human oversight. The Act also envisions enforcement by national regulators and coordination across Member States, marking an ambitious move to harmonize AI risk management.

In the United States, AI governance leans toward a decentralized, sector-by-sector model. Rather than a single omnibus framework, regulation is emerging through existing agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, FDA, and others, complemented by voluntary guidelines from industry-led consortia. This model allows innovation to move fast but raises concerns about fragmented oversight.

China, meanwhile, has adopted a top-down governance approach. The government uses regulatory mandates and national strategy to steer AI deployment, especially in strategic sectors like surveillance, smart cities, and public services. Control, as much as innovation, is embedded in Beijing’s governance philosophy.

Across all these jurisdictions, common lessons emerge: first, a one-size-fits-all regulatory model does not work. Risk must be assessed, categorized, and mitigated. Second, transparency is essential; AI systems should be auditable and understandable. Third, governance must be multi-stakeholder, incorporating industry, civil society, academia, and government.

Yet, despite these advances, most frameworks remain untested at scale. Experts note that laws struggle to keep up with the pace of AI innovation. In lower and middle-income countries, the challenge is compounded by resource constraints, limited technical expertise, and dependency on technology developed abroad.

Risks and challenges specific to Ghana and Africa

While Ghana’s ambitions for AI are bold, the country must also grapple with specific risks shaped by local realities.

- Data bias and quality – Many AI models in Ghana are trained on datasets sourced from abroad. These models may not adequately reflect Ghanaian societies, leading to biased outcomes, for instance, in credit scoring or healthcare predictions. Without concerted effort to generate high-quality local data, Ghana risks importing systemic errors embedded in foreign-trained models.

- Transparency and explainability – AI systems, particularly in high-stakes areas like public service delivery or justice, need to be interpretable. However, many machine-learning models act like black boxes. If a citizen’s access to public support or benefits is determined by such a system, there must be mechanisms to audit decisions, attribute responsibility, and provide recourse.

- Regulatory fragmentation – Ghana is developing multiple digital laws simultaneously, including the Emerging Technologies Bill, proposed updates to data protection laws, and cybersecurity changes. Policy experts warn that these overlapping legislation may create fragmented authority across agencies, leading to compliance friction and reduced clarity. Moreover, novel requirements like algorithmic bias testing sometimes clash with privacy protections, creating a bias-testing paradox.

- Capacity constraints and infrastructure gaps – Building a world-class AI ecosystem requires talent, but Ghana currently faces limited availability of AI professionals, data scientists, and researchers deeply rooted in local contexts. Furthermore, infrastructure challenges such as inconsistent electricity, limited compute capacity, and uneven internet access hinder large-scale deployment of advanced AI.

- Sovereignty and data localization – Ghana’s Ministry of Communications, Digital Technology and Innovations has already emphasized the importance of anchoring AI on local datasets to avoid over-dependence on foreign models. This is not just a technical demand but a sovereignty concern: if Ghanaian data is exported or controlled exclusively by foreign entities, the country risks ceding control of its digital future.

Why Ghana should lead on AI governance?

Given these opportunities and risks, Ghana has both a strategic interest and ethical responsibility to lead AI governance in Africa.

- Strategic advantage – Ghana’s youthful population, growing digital infrastructure, and dynamic innovation ecosystem present a strong foundation for leadership. The One Million Coders Program and other digital-skilling initiatives are building a pipeline of talent capable of supporting homegrown AI development.

- Moral and development imperative – AI governance is not only about regulation; it is about justice, inclusion, and dignity. Ghana has the opportunity to ensure that AI systems are aligned with local values, respecting culture, identity, and democratic rights. Leading in this space could also help mitigate economic inequalities by preventing exploitative or biased AI.

- Geopolitical and soft power leadership – By establishing sound governance frameworks, Ghana can become a model for other African nations. Its success could catalyze a continental movement toward responsible AI, a soft power that supports Ghana’s influence in continental policy forums and continental digital integration initiatives.

- Economic opportunity – Clear governance reduces risk for investors and unlocks capital. International investors, impact funds, and AI enterprises are more likely to commit to markets where regulations are understood and stable. Ghana’s leadership in AI governance could thus help attract high-quality investment into its digital economy.

Lessons from other jurisdictions

Ghana does not need to reinvent the wheel. There are best practices from around the world that can guide its path.

- European Union – Risk-based regulation – The EU’s AI Act demonstrates a sophisticated risk-based approach. By categorizing AI systems by their potential for harm and imposing tailored obligations for high-risk applications, the EU model balances innovation with protection. Mandatory transparency, conformity assessments, and human oversight are central to its design.

- Singapore and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – Multi-stakeholder governance and sandboxes – Singapore and OECD member states emphasize regulatory sandboxes and multi-stakeholder advisory councils. These structures allow governments to test new technologies in controlled environments while learning from the private sector and civil society. This ensures governance evolves with innovation rather than lagging behind it.

- Contextual ethics – African insights – Analyses produced by institutions such as Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) argue that governance frameworks in Africa must be human-centric and culturally grounded. African values such as communitarianism, relational trust, and respect for local knowledge should inform AI governance. This perspective avoids simply copying Western models and ensures that AI serves local needs.

- Localizing trust – Recent research into African conceptualizations of trust in AI shows that trust is deeply shaped by community values and relational bonds rather than individualism common in Western discourse. Integrating these worldviews into governance helps design systems people can actually trust.

Policy recommendations and roadmap for Ghana

To deliver on the ambition of becoming Africa’s AI governance leader, Ghana must act strategically and decisively by adopting some the following recommendations amongst others:

- Harmonize legislation – Align the Emerging Technologies Bill, Data Protection Act, Data Harmonization Bill and Cybersecurity Bill amendments to avoid jurisdictional overlap. Create clear institutional roles, for instance by empowering a centralized agency to coordinate AI regulation.

- Establish a governance body – Flowing from above, there is a need to create an independent AI Commission or Agency responsible for standard setting, overseeing impact assessments, certifying systems, and conducting audits. This body should include representatives from government, academia, industry, civil society, and local communities.

- Mandate ethical safeguards – Require all high-risk AI systems to undergo algorithmic impact assessments for fairness, bias, privacy, and environmental impact. Enforce standards for system explainability, transparency reports, and redress mechanisms.

- Build local data infrastructure – Invest in data infrastructure, including a national data exchange or clearinghouse, to nurture the creation of datasets that reflect Ghana’s diversity. Prioritize anonymization, interoperability, and governance principles that protect digital sovereignty.

- Develop technical capacity – Scale programs like the One Million Coders initiative to build a large base of AI developers, ethicists, and governance professionals. The Government can also take the further step of funding AI research hubs in universities and partnerships with international institutions.

- Launch regulatory sandboxes – Establish testing environments for AI innovations similar to the sandboxes launched by both the Bank of Ghana and Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC) where startups and established firms can trial systems under supervision and in a controlled setting. Use these sandboxes to refine regulatory norms and collect data for policy learning.

- Lead regionally – Propose a West African or African AI Governance Forum under AU, ECOWAS, or Smart Africa frameworks. Champion regional standards, cross-border data policies, and shared regulatory infrastructure.

Conclusion

Ghana stands at a pivotal moment. The global AI race is not just about technological supremacy; it is about shaping how societies will live, work, and interact in the decades ahead. By leading on AI governance, Ghana can achieve more than national leadership; it can set a model for the rest of Africa, embedding its values, protecting its people, and unleashing human-centered innovation.

But leadership will not emerge by accident. It will require deliberate policymaking, inclusive institution building, coherent legal reforms, and sustained investment. It will require public-private partnerships, multi-stakeholder engagement, and courage to regulate new technologies in a way that balances risk with opportunity. If Ghana plays its cards right, it will not only benefit from AI’s transformative power; it will shape that power. And in doing so, it will offer a blueprint for the continent: a future where AI strengthens democracy, drives prosperity, and reflects African aspirations.

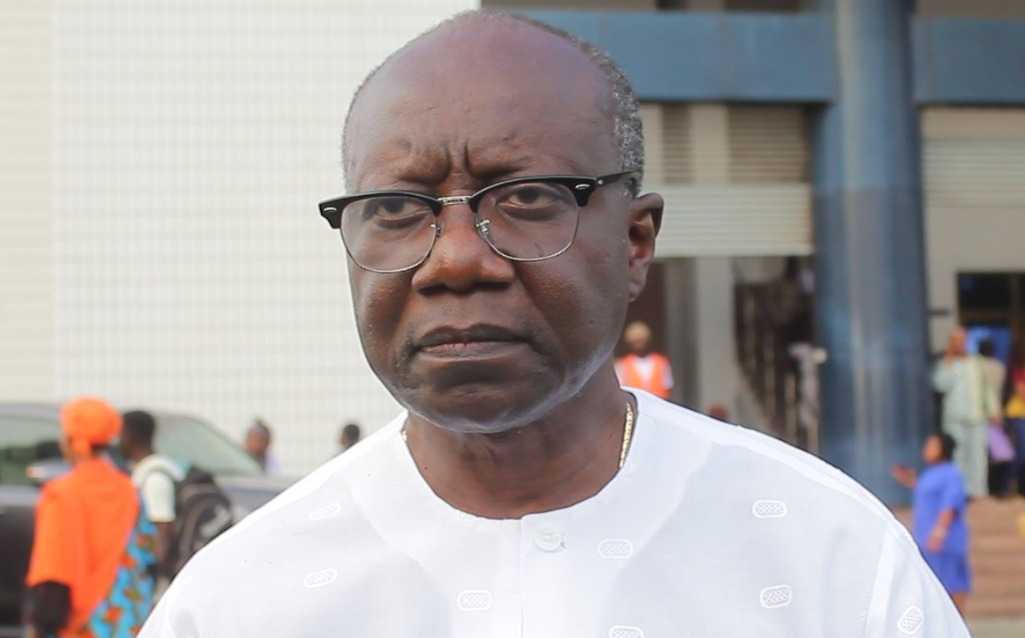

>>>the writer is an Associate with SUSTINERI ATTORNEYS PRUC with its Corporate, Governance and Transactions Practice Group, specializing in legal service provision for Startups/SMEs, Fintechs and Innovations. He welcomes views on this article via [email protected]

The post Learning from the global AI race: Why we must lead on AI governance in Africa appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS