The U.S. State Department trusts foreign governments to nominate reputable honorary consuls, despite global accounts of wrongdoing.

The U.S. State Department trusts foreign governments to nominate reputable honorary consuls, despite global accounts of wrongdoing.

The deal to pay off the treasurer of Detroit was forged in a booth at a strip club named Bouzouki.

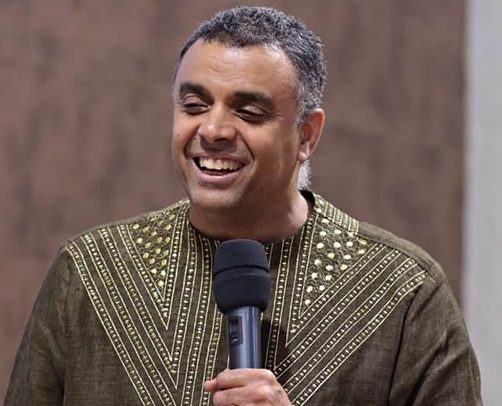

“You’re basically paying all these other guys. … You should be paying me,” the city’s treasurer told local business owner Robert Shumake that day in 2007 during a conversation that Shumake would later recount to federal prosecutors.

Shumake, a self-described community organizer and philanthropist, agreed to make payments to several officials who ran the city’s pension funds. The money was used, among other things, to cover gambling expenses, airline tickets and a day cruise to the Bahamas.

In return, Shumake received a lucrative reward: Detroit steered millions of pension dollars to his investment company and paid him $1.2 million in fees. Prosecutors would later say it was “the worst possible deal for the pension systems.”

A series of city officials and businessmen were convicted in the sweeping scandal, but Shumake struck a deal in exchange for his testimony in 2011 and avoided prosecution.

Soon after, he landed another fortunate break. The southern African country of Botswana nominated him as an honorary consul in the United States, a diplomatic position that came with legal protections, travel benefits and political connections unavailable to most Americans.

The State Department approved the appointment, granting Shumake entry into the privileged world of international diplomacy. Honorary consuls, though not as prominent as ambassadors and other career diplomats, have for centuries worked from their home countries to represent foreign nations.

The department did not respond to questions about what steps, if any, it took to review Shumake’s background. Had officials done even a cursory internet search, they would have discovered that Shumake’s real estate broker’s license was suspended in 2002 and that he settled a bank fraud case in 2008, agreeing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Shumake was among at least 500 current and former honorary consuls in the United States and around the world who have been implicated in criminal investigations or other controversies — including scores named to their posts despite past convictions or other red flags, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and ProPublica disclosed in a series of stories this year.

Reports of exploitation, scandal and criminal behavior by the little-known volunteer diplomats have surfaced for years. But the vast majority of governments have failed to strengthen oversight or press to reform the international law that protects thousands of honorary consuls worldwide, a new review found.

All told, the Shadow Diplomats investigation identified criminal or controversial consuls connected to at least 168 governments, including Russia, which has leveraged the system to install dozens of pro-Kremlin advocates on foreign soil as a soft-power strategy.

In the wake of the reporting, Paraguay, Finland, Brazil and other countries announced investigations of consuls and the system that empowers them. In some cases, government officials acknowledged not knowing how many consuls they had appointed or whether any had been convicted of crimes.

Experts in international diplomacy and national security say that more governments must demand change, examine nominees before they are approved and track their activities once they become consuls.

ProPublica and ICIJ identified more than 150 current and former consuls accused or convicted of tax evasion, fraud, bribery, corruption or money laundering. Nearly 60 were tied to drug or weapons offenses, at least 20 others to violent crimes and 10 to environmental abuses. Thirty honorary consuls have been sanctioned by the United States and other governments; nine have been linked to terrorist groups by law enforcement and governments. Once accused, dozens of consuls have invoked their status to avoid prosecution, police inquiries or fines.

“No one is checking them out,” said Bob Jarvis, an international law and constitutional law professor at Florida’s Nova Southeastern University who first examined the honorary consul system in the 1980s. “What are we doing? Who are these people?”

The United States does not appoint its own honorary consuls overseas but has for decades allowed foreign countries to appoint U.S. citizens as consuls in America. An estimated 1,100 were in place this year.

The State Department, responsible for approving consul nominations, noted years ago that the United States was “not in a position” to conduct background checks or analyze the qualifications or suitability of nominees on U.S. soil and instead entrusted foreign countries to review credentials.

Unlike some other countries, the United States has no code of conduct for honorary consuls. The State Department previously fought an effort by Congress to review whether diplomatic pouches, protected from searches under international law, had been used to move contraband. The department at the time said the measure would impact U.S. diplomats overseas.

Unlike some other countries, the United States has no code of conduct for honorary consuls. The State Department previously fought an effort by Congress to review whether diplomatic pouches, protected from searches under international law, had been used to move contraband. The department at the time said the measure would impact U.S. diplomats overseas.

In 2020, the department reached out to foreign embassies with a simple request: an updated list of their honorary consuls in the United States. The last time the department inquired was five years earlier, records show.

“You’re looking at a pretty large universe, so to engage in a detailed review for every nominee would be rather difficult,” Lawrence Dunham, former assistant chief of protocol at the State Department, said in an interview.

The State Department did not respond to specific questions about its oversight of consuls. In a statement, Cliff Seagroves, principal deputy director of the Office of Foreign Missions, said the department works to “protect the U.S. public from abuse of diplomatic privileges and immunities. This oversight includes the accreditation of honorary consuls and their performance of official duties in the United States. The Department has zero tolerance for evidence of inappropriate activity by any member of a foreign mission, including honorary consuls.”

The department did not respond to questions about the appointment of Shumake.

Shumake did not respond to questions about his activities before becoming consul. He has previously said he cooperated with the government in the pension case; Detroit’s former treasurer was sentenced in 2015 to 11 years in prison.

Shumake has also said he never sought to misrepresent his professional background. He has denied wrongdoing in the bank fraud probe.

Outside the United States, a small number of governments faced with scandals have adopted more stringent protocols for appointing and accepting honorary consuls.

Three years ago, the Canadian government launched a review after Syrian refugees in Montreal discovered newly approved honorary consul Waseem Ramli in a red Hummer fitted with an image of the Syrian flag and a picture of President Bashar al-Assad, whose regime has killed tens of thousands of civilians through airstrikes and chemical weapons.

“To us, that is not the Syrian flag. It represents horrors for us. It represents evil,” said Farouq Habib, a Syrian father of two who was granted asylum in Canada. “It was shocking for me to see it on the streets of Canada. How can Canada adopt someone … without any due diligence or vetting? It undermines the credibility of the system itself.”

The Canadian government dismissed Ramli before his term began and reported that consuls appointed by 15 countries warranted closer scrutiny.

Ramli could not be reached for comment. At the time of his nomination, he said he would represent Syrians regardless of their political views.

“I need some [information] on what happened to let this one pass,” a Canadian official wrote at the time, according to emails released by the government. “Where did we ‘fail?’”

Outside the United States, a small number of governments faced with scandals have adopted more stringent protocols for appointing and accepting honorary consuls.

“The Honor System”

The honorary consul system was created with great promise centuries ago, when governments began to promote their cultural and economic interests in foreign countries by appointing prominent private citizens to serve as liaisons from their home countries. Under international law, when a foreign government nominates a consul, local governments must in turn approve the appointment.

Many consuls are diligent advocates, forging country-to-country alliances in the arts, industry, science and academia while drawing far less attention than ambassadors and other career diplomats.

But the perks of diplomacy have long attracted some dubious appointees. Honorary consuls receive legal immunity in matters involving their work. Their correspondence cannot be seized, and their offices and consular bags are protected from searches. Their status provides access to leaders of politics and industry.

In the United States, an honorary consul for Malaysia tried to use his diplomatic status to get out of a $10 traffic ticket in Portland, Oregon, taking a lawsuit to the state’s Court of Appeals in 1979 before he lost, court records show.

In Los Angeles in the 1990s, honorary consul Latchezar “Lucky” Christov conspired with lawyers, a firefighter, a police officer and a rabbi, among others, to help move tens of millions of dollars for a Colombian drug cartel.

To avoid unwanted attention, Christov planned to pick up drug money in a car with a diplomatic license plate, records show. He also held cash in his office on Wilshire Boulevard, where the sign over the door read: Consul Bulgaria.

Christov, whose exploits were later described in a report to Congress, pleaded guilty to laundering drug money. He died in 2015.

In 2005, an honorary consul representing the Czech Republic in Michigan and Ohio tried to avoid paying property taxes on a 16,000-square-foot home near Detroit with a six-car garage and elevator. He argued the property had been transferred to the Czech government.

“Does the embassy pay property taxes? Of course not! Does the consulate in New York pay property taxes? Of course not!” Thomas Prose was quoted as saying at the time. Local officials denied a tax exemption, and Prose resigned as honorary consul. Prose could not be reached for comment; he previously said he paid the taxes “out of goodwill.”

One of the more high-profile honorary consuls in the United States was Jill Kelley, who gained notoriety in 2012 for triggering an FBI investigation that ultimately exposed an extramarital affair between then-CIA Director David H. Petraeus and his biographer.

During the media coverage, Kelley reportedly called 911 to complain about trespassers. “I’m an honorary consul general … so they should not be able to cross my property,” she said.

Kelley, appointed consul by South Korea, lost her consul post that year. At the time, a New York businessman said she had sought millions of dollars to help him win a gas contract in South Korea.

“It’s not suitable to the status of honorary consul that (she) sought to be involved in commercial projects and peddle influence,” South Korea’s deputy foreign minister told the Seoul-based news agency Yonhap.

Kelley denied wrongdoing, telling ProPublica and ICIJ that she did not monetize her role as honorary consul. “I never made a dollar or capitalized from my work,” she said.

In response to questions, Kelley shared a copy of a 2013 civil lawsuit that she and her husband filed against the U.S. government, alleging their privacy was violated by the disclosure of “personal, private and confidential information” during the Petraeus scandal. The loss of her consulship deprived Kelley of “years of significant public service, social and financial opportunities,” according to the lawsuit, which she later dropped. Kelley declined to elaborate.

In recent years, more than 100 countries, including Russia, Guatemala, Liberia and Malta, have had consuls in the United States, State Department records show. France had the most: 53 as of March.

“I cried at the time. How come this person was appointed?” said Muzna Dureid, a Syrian refugee. “Even in Canada, we don’t feel safe.”

The State Department has several requirements, including that a consul is 21 or older, a U.S. citizen or permanent resident and holds no government position with duties that could conflict with the post.

A State Department memo to foreign embassies in 2003 noted that the U.S. government “trusts” foreign countries to completely review the credentials of nominees. Once consuls are in place, the memo said, they would remain accountable to the governments they represent.

“It’s on the honor system,” Dunham said.

He added that the United States can always refuse to accept honorary consul nominees or, later, remove them from their posts.

Efforts to strengthen oversight of diplomatic privilege over the years have been sporadic. In the 1980s, the State Department enacted a one-year moratorium on the appointments of new honorary consuls in response to concerns from Congress about the number of people in the U.S. with diplomatic protection.

Around the same time, a bipartisan group of U.S. lawmakers sought to review whether diplomats were exploiting protections that allowed them to receive bags, boxes and containers in the United States without inspection. Under international law, diplomatic pouches are protected from scrutiny, even by X-ray.

The measure would have required the government to adopt safeguards to ensure bags were not used to smuggle drugs, explosives, weapons or any other materials used to advance terrorism.

“We are concerned that terrorists could, and we have every reason to believe, have shipped under the protection of diplomatic immunity pouches carrying such items as small armed weapons and explosives to be used against law enforcement officers,” Dennis Martin, then-president of the American Federation of Police, testified at a congressional hearing.

The State Department opposed the measure, arguing that the United States was the largest sender of diplomatic pouches. “The beneficiary of diplomatic immunity fundamentally is the United States government because our personnel abroad could not function without it,” the department’s head of protocol said.

The measure died in Congress.

Last year, the department requested that states stop issuing special license plates to honorary consuls, saying they “may imply privileges and immunities to which honorary consular officers are not entitled.”

Some states, however, are still issuing the plates, including Oregon, Arizona and Georgia, ProPublica and ICIJ found. Texas has issued or renewed more than 3,900 plates to honorary consuls since 1994, records show.

One financial crime expert pointed to another vulnerability.

Some foreign governments have chosen to classify honorary consuls as “politically exposed persons” who present a higher risk of financial crime and are more closely scrutinized by financial institutions.

The United States has not done so, leaving that determination to financial institutions.

“An honorary consul can be used much like a gatekeeper,” said Sarah Beth Felix, a former banking compliance executive. “It’s a great way to run dirty money because honorary consuls are typically not tagged as higher risk in a monitoring system and they get the benefit of not being subjected to law enforcement searches.”

The Treasury Department said that U.S. regulations do not define politically exposed persons. “Whether honorary consuls are PEPs depends on the facts and circumstances surrounding the consul’s appointment and role,” said Jayna Desai, spokesperson for the department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

Worldwide warning signs

For years, government investigations around the world have chronicled lawlessness and abuse among consuls that appear to eclipse incidents in the United States.

Twenty-five years ago, Bolivia announced a review of the honorary consul system there after high-profile scandals, including one in which the country’s consul in Haiti was dismissed after police reportedly found an arsenal of weapons inside the consul’s home, including rifles, pistols and a grenade launcher. Authorities suspected that the consul was linked to paramilitary groups fighting against the Haitian government, local media reported.

“It is well worth reviewing completely this outdated custom of honorary consuls,” local newspaper La Razón wrote after the arrest in an editorial titled “The Chronic Problem of Honorary Consuls.”

“It is a thousand times preferable not to have anyone to represent us in a nation than to go through undignified situations,” the newspaper wrote.

In 2003, Hungary overhauled its system after a stockbroker wanted for fraud and embezzlement fled the country in an honorary consul’s Mercedes. The stockbroker also held an ID card from another honorary consulate, according to media reports.

After the incident, the Hungarian government announced a review of the honorary consul system and stopped issuing identity cards to employees of honorary consulates. The stockbroker was convicted and jailed for five years; the consuls were not charged.

In 2007, Liberia dismissed nearly all of its consuls overseas after reports from Europe, Asia and the Middle East of drug smugglers and money launderers holding honorary consul passports, according to a U.S. State Department cable at the time.

In 2007, Liberia dismissed nearly all of its consuls overseas after reports from Europe, Asia and the Middle East of drug smugglers and money launderers holding honorary consul passports, according to a U.S. State Department cable at the time.

In 2019, Canada became one of the largest governments to review the system, initiating the probe after reports about Ramli, nominated by Syria, surfaced in Montreal.

“I cried at the time. How come this person was appointed?” said Muzna Dureid, a Syrian refugee. “Even in Canada, we don’t feel safe.”

The government investigation found that “time constraints and lack of information management expertise” limited an initial review of Ramli, who went on to say in an interview with Maclean’s magazine that a prominent Syrian volunteer rescue group was a “terrorist organization.”

Canada introduced a new process to examine and appoint honorary consuls, adding a code of conduct.

A family of Consuls

Despite the findings by governments, most countries have not called for widespread reforms. That includes Spain, where authorities are currently investigating three honorary consuls accused of helping to launder money for Simón Montero Jodorovich, an accused drug dealer.

In a 2,000-page report, police wrote in 2019 that the consuls representing Mali, Croatia and Albania allegedly called Jodorovich “big boss.”

Honorary consuls, the police reported, work without pay for the countries they represent. “What is obtained,” police wrote, “is compensation in terms of prestige, privileges and social relations, not to mention the coveted diplomatic bag … that crosses borders without any control.”

The consuls, who have not been criminally charged, have denied wrongdoing. An attorney for Jodorovich said his client is innocent and “has never manipulated any consul,” adding that Jodorovich’s relationship with them was transactional.

In Central America, the government of Honduras has previously reviewed its honorary consuls overseas, but consuls within the country have received less attention.

The powerful Kafie family has counted eight honorary consuls among its members, representing an eclectic group of countries that include Finland, Latvia and Panama.

In 2015, Schucry Kafie, a prominent businessman who has served for years as honorary consul for Jordan, was arrested in a Honduran corruption scandal, accused with others of overcharging the government for medical supplies.

Others implicated in the scandal were detained, but Kafie was released by a judge, who noted that his status as consul required him to sometimes leave the country, court records show.

The charges against Kafie were ultimately dismissed.

In a written statement, Kafie said that the government’s case was politically motivated and that the company did not overcharge for equipment. He added that the court allowed him to leave the country for health reasons and not because of his job as honorary consul.

In Panama, the Kafie family has a power plant that has for years drawn complaints from nearby residents, who say they fear it emits toxic gas.

Martin Ibáñez, 66, said his skin itches and his eyes burn from the smoke. He has written to the Panamanian government and others, hoping someone will determine whether the plant is operating safely.

“It’s like they dropped an atomic bomb,” he said this year. “I will die one of these days, but I want to go down fighting.”

Kafie said the plant did not cause health problems.

“Harm and abuse”

In 2020, the United Nations Institute for Training and Research offered a course for honorary consuls that explored diplomatic law and ethics.

“Without a strong governance and reporting process, honorary consuls can become isolated and remote and their activities can be contrary to the interests of the sending state,” the institute noted at the time.

The course was offered only once. An institute official told ProPublica and ICIJ that there were not enough participants.

Diplomatic law experts said governments should require training and also make public the names and locations of honorary consuls. Of more than 180 countries that appoint and receive honorary consuls, only 42 publish up-to-date information, including names of consuls. Dozens of countries report no information at all, ProPublica and ICIJ found. Governments could also introduce an honorary consul code of conduct, evaluate the records of those currently holding the posts and start investigating new nominees, experts said.

“The harm and abuse,” said Jarvis, the law professor from Florida, “far outweighs whatever benefit the system is providing.”

In Michigan, Shumake’s honorary consul post for Botswana ended in 2015. He had also been appointed honorary consul by the government of Tanzania; that post ended in 2015 as well.

While consul, he won a contract to build a rail line in Tanzania in a deal that opponents criticized as improper and opaque. Shumake defended the project; the rail line was never built.

The Botswana Ministry of Foreign Affairs told ProPublica and ICIJ that Shumake’s tenure was terminated after the U.S. State Department disclosed that he had been accused of misconduct. The ministry did not elaborate. The government of Tanzania did not respond to requests for comment.

One year after the consul posts ended, U.S. authorities seized more than $250,000 in cash at the Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina from one of Shumake’s associates. The money was stashed in a carry-on bag, which later tested positive for traces of cocaine, according to documents from a subsequent civil forfeiture case.

The courier referred authorities to Shumake, who said he had raised the money to support communities in Africa and the Caribbean and that as “an ambassador” of an international commission, he had diplomatic immunity in transporting it, according to court documents. Authorities seized the cash.

Shumake declined to respond to detailed questions from ProPublica and ICIJ, but he said the U.S. returned the money. Court records show the government agreed to return half the money to the international commission.

In an unrelated case in 2017, Shumake pleaded guilty to misdemeanor violations in a Michigan court after his mortgage auditing company was accused of improperly taking fees from distressed homeowners.

“You preyed on people at their lowest possible moment,” a county judge told Shumake at his sentencing hearing.

Last year, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission alleged that Shumake and others had set up a fraudulent crowdfunding scheme that promised investors profits from the cannabis industry. The SEC filed a lawsuit, which is ongoing. Shumake has denied wrongdoing.

In May, seven years after his honorary consul positions ended, he posted a video online titled “Robert Shumake Holds the Titles of Honorary Consul.” The video includes an image of two men shaking hands — while exchanging wads of cash.

By Will Fitzgibbon, ICIJ; Debbie Cenziper, ProPublica; and Eva Herscowitz, Emily Anderson Stern and Jordan Anderson, Medill Investigative Lab

Reporting was contributed by Jennifer Avila, Jesus Albalat, Robert Cribb, Atanas Tchobanov, Zsuzsanna Wirth, Delphine Reuter, Nicole Sadek and Michael Korsh, Hannah Feuer, Michelle Liu, Grace Wu, Linus Hoeller, Dhivya Sridar, Quinn Clark, Henry Roach, Evan Robinson-Johnson, Susanti Sarkar, Margaret Fleming, Julian Andreone, Sela Breen and Belinda Clarke, of the Medill Investigative Lab.

The post Shadow diplomats have posed a threat for decades: But governments looked the other way appeared first on Ghana Business News.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS